A New Department Of Energy

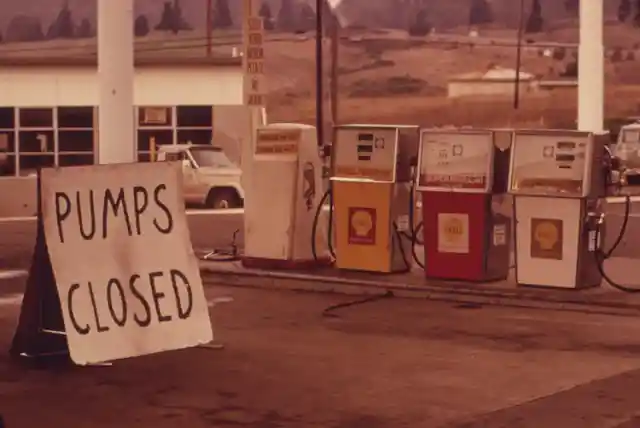

In 1973, the United States found itself dealing with an Arab oil embargo that sent the U.S. economy reeling, caused fuel shortages, and quadrupled oil prices. Filling gas tanks was a task in and of itself, as long lines at gas stations became a commonplace and aggravating sight.

The Yom Kippur War in October 1973 served as the catalyst for the embargo, when a coalition of Arab states, led by Syria and Egypt, launched an attack on Israel on the holiest day on the Jewish calendar. The Soviet Union then resupplied Syria and Egypt, its allies, which prompted the United States to respond by providing massive supplies in order to assist Israel. The action didn’t go unnoticed: Members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) retaliated with an oil embargo against the United States as well as the Netherlands, Israel’s two main supporters at that time.

The resulting energy crisis rocked the U.S. economy and forced American leaders and researchers to develop a wide range of energy solutions that would ultimately impact policymaking, technology, and architecture. But the energy conundrum also resulted in important changes that would impact energy efficiency, building designs, and government policies in both the short and long-term.

In 1977, U.S. President Jimmy Carter proposed the creation of a new Department of Energy that would be charged with meeting the challenges of a radically changing energy landscape in the country.

“The energy crisis has not yet overwhelmed us, but it will if we do not act quickly,” Carter said. “Both consumers and producers need policies they can count on so they can plan ahead. This is one reason I am working with Congress to create a new Department of Energy, to replace more than 50 different agencies that now have some control over energy.”

Later that same year, Carter signed into law the Department of Energy Organization Act, which assembled the new federal energy programs under one roof, so to speak. The department noted that, “[the Act] provided the framework for a comprehensive and balanced national energy plan.”

As a result of these initiatives, the U.S. government was in a better position to coordinate federal policy having to do with current or future energy crises. In addition, the department is home to the Office of Nuclear Energy.

Energy-Saving Windows

In response to the energy crisis, the Energy Department funded research to create low-emissivity (low-E) window coatings, which today are standard on many clear glass buildings. The Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, a Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory managed by the University of California, collaborated with the window industry to develop energy-efficient windows. The new coatings proved effective at moderating indoor temperatures by holding in heat during the colder months and preventing interior overheating during warmer weather.

According to the Energy Department, more than 50 percent of commercial window sales and nearly 80 percent of residential window sales incorporate low-E coatings. As a result, energy use can be reduced by as much as 40 percent, saving businesses and consumers billions of dollars in energy costs.

Physicist Steve Selkowitz, who was instrumental in the development of low-E window coatings, explains that, “The concept and some of the materials and patents were already out there. But the theory had to be turned into practice—moving from a good idea to viable products and production processes that could be deployed at scale to save large amounts of energy at affordable costs.”

Lowered Thermostats

The energy crisis also forced the U.S. president to make energy conservation and energy efficiency national priorities. In a 1977 fireside chat, Carter sported a cardigan sweater which was considered exceptionally casual attire for a sitting U.S. president and urged people to keep their home thermostats at 65 degrees during the day and 55 degrees at night in order to help ease a winter natural gas shortage.

In an April 1977 speech, Carter warned of a possible “national catastrophe” if Americans proved unwilling to make the sacrifices necessary for curtailing energy consumption.

“With the exception of preventing war, this is the greatest challenge that our country will face during our lifetimes,” said Carter.

Solar Panels At The White House

In response to the energy crisis, Carter had solar panels installed on the roof above the West Wing of the White House in 1979. Today, many experts agree that Carter was ahead of his time when it came to focusing on and shifting to clean and renewable energy.

“A generation from now,” Carter said, “this solar heater can either be a curiosity, a museum piece, an example of a road not taken, or it can be a small part of one of the greatest and most exciting adventures ever undertaken by the American people—harnessing the power of the sun to enrich our lives as we move away from our crippling dependence on foreign oil.”