Khomeini’s Rise To Power Leads To Hostage Taking

It all began with the overthrow of Mohammad Raza Pahlavi as shah of Iran and the subsequent rise to power of Ayatollah Khomeini.

When Pahlavi was diagnosed with cancer, he was encouraged to come to the United States to undergo treatment. Because he had been accused of crimes against Iranian citizens, Iran issued demands for his return, which the U.S. rejected. Consequently, Iran believed that the U.S. was trying to undermine the Iranian Revolution and that granting Pahlavi immunity amounted to U.S. complicity in Pahlavi’s atrocities. Eventually, Pahlavi left the U.S. and was granted asylum in Egypt, where he died on July 27, 1980.

The full ramification of Pahlavi’s relationship with the U.S. had yet to be realized.

When Ayatollah Khomeini came to power in Iran, the country’s anti-Western sentiment significantly increased. After Pahlavi came to the U.S., Khomeini’s anti-American rhetoric included calling America the “Great Satan.” In an attempt to leverage the return of Pahlavi to Iran and to force the release of frozen Iranian assets in the U.S., Khomeini appeared to sanction the taking of hostages at the U.S. embassy in 1979.

On the date the hostages were taken, Iranian student unions loyal to Khomeini had organized a demonstration beyond the walls of the compound. Originally planned as a symbolic and peaceful occupation, the gathering grew in size and became increasingly marked by angry demands.

Eventually, hostage-takers climbed the embassy wall, at which time a group of six diplomats evaded capture, as they were working in a separate building in the compound. The six diplomats, rescued by a joint CIA-Canadian effort dubbed the “Canadian Caper,” eventually managed to depart Tehran and board a Swissair flight to Zürich.

Hostages On The Move

The hostage takers originally planned to hold the embassy for only a short time, but as the popularity of the takeover increased, as did Khomeini’s support for it, the hostage situation escalated and continued way past its original intended deadline.

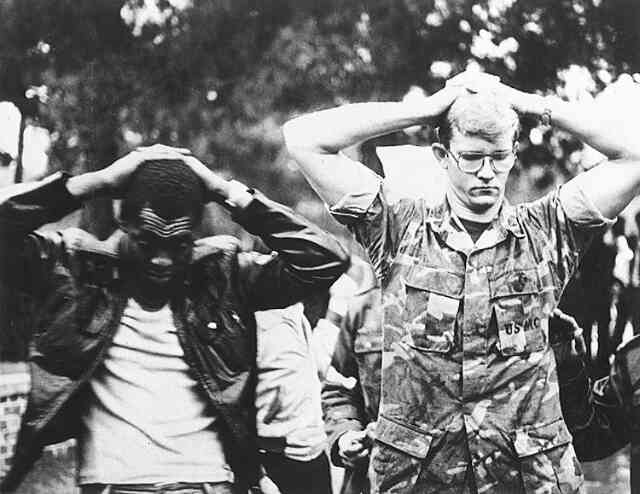

On November 19, 1979, the hostage takers released two African Americans and one woman because they claimed solidarity with “oppressed minorities”; the next day, four more women and six African Americans were released. A single African American hostage remained, and one white man, Richard Queen, was released after becoming seriously ill. All of the remaining hostages were originally held in the embassy but eventually were moved to prisons in Tehran in an attempt to foil any possible escapes or the implementation of rescue plans. In November 1980, they were moved to the Teymur Bakhtiar mansion in Tehran, where they remained until their release.

Although Iranian propaganda reported that the hostages were always treated respectfully, the hostages themselves described enduring abuse, beatings, solitary confinement, the binding of their hands for days or weeks, and even mock executions.

Efforts At Diplomacy Fail

President Carter initially appealed for the release of the hostages on humanitarian grounds; all such attempts failed. On November 12, 1979, he enacted an oil embargo, and on November 14, nearly $8 billion in Iranian assets were frozen. After all such attempts at hostage release failed, Carter ordered the U.S. military to attempt a rescue mission.

Operation Eagle Claw employed warships to attempt a rescue, but on April 24, 1980, the rescue mission failed, leaving one Iranian and eight American servicemen dead. A second planned rescue attempt was never executed.

After the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war in September 1980, Iran entered into negotiations with the U.S., and the Algiers Accords were signed on January 19, 1980. The following day, the hostages were released moments after Ronald Reagan was sworn in as president of the United States. Of the 66 individuals who had been taken hostage, 13 were released on November 19 and 20, 1979; one was released on July 11, 1980; and the remaining 52 were released on January 20, 1981.

The Days, And Years, After The Hostage Taking

After their release, the hostages were flown first to Algiers and then to Rhein-Main Air Base in West Germany; they later entered the Air Force hospital in Wiesbaden where they underwent medical check-ups and debriefings. Acting as an emissary, President Carter was on site to receive the hostages as they arrived. The hostages received a hero’s welcome when they finally returned to the U.S.

Iran’s government and affiliated groups now use the former U.S. Embassy building, and, as of 2001, it has been designated as a museum of the revolution. As a result of the hostage crisis, the U.S. and Iran severed diplomatic relations.