The Beginning Of A Movement

“I have a dream.”

The words have resonated throughout the United States – even the world – since the historic 1963 March on Washington, a seminal moment in the civil rights movement.

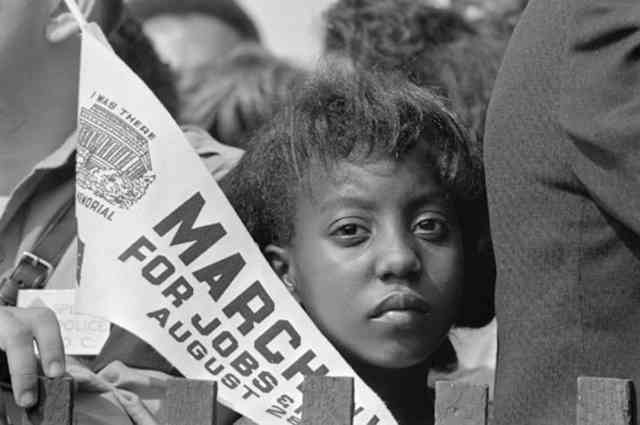

During the 1960s, it became clear that African Americans continued to faced widespread discrimination: in fact, state-endorsed segregation in the form of Jim Crow laws was still the law of the land. But then came August 28, 1963, and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (as the event was officially known) shined a light on inequities and discrimination that had been in place for far too long. The March ultimately led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both of which brought about monumental changes in how people of color were viewed, respected, and treated, in the U.S.

Racial discrimination, along with subsequent economic, social, and political repression, had long been a fact of life for African-Americans. During the 1940s and 1950s, calls for racial equality resulted in widespread demonstrations and political protests advocating for the civil rights that had been denied to African Americans for far too long. Several protests took place at the nation’s capital, drawing the attention of the media and lawmakers, and ultimately setting the stage for the 1963 March on Washington.

Some of the protests and exchanges became violent, and many civil rights leaders believed that peaceful protests would be more effective at garnering positive public attention and support. After several attacks on civil rights protesters in Birmingham, Alabama, in early 1963, it became apparent that that a large scale, peaceful protest was needed in order to send a clear message to Washington lawmakers.

The Times They Are A-Changin’

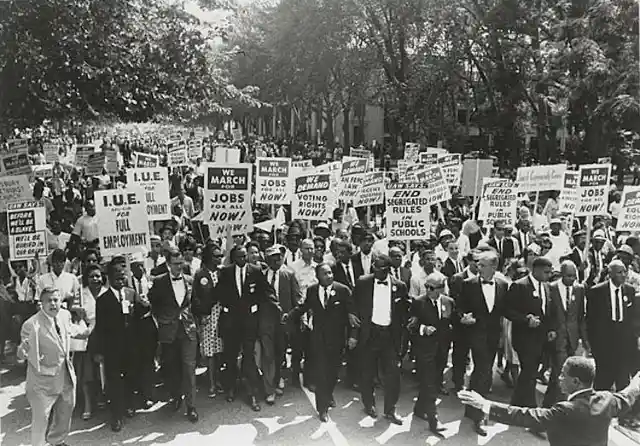

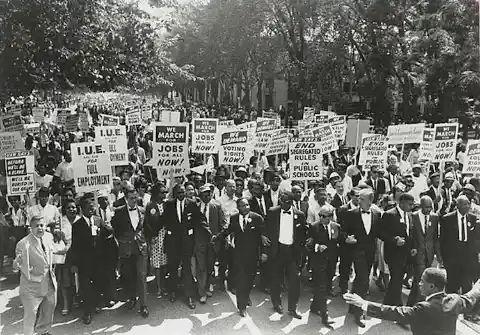

In the spring of 1963, A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, president of the Negro American Labor Council, and vice president of the AFL-CIO, contacted Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to inform him that he was planning a march on Washington to protest job discrimination. King agreed to help plan and organize the event, and President John F. Kennedy was notified that the march would take place at the capital on August 28, 1963. In addition to shining a light on job discrimination, the event was to serve as a tipping point for a comprehensive civil rights bill.

More than 250,000 people, about 75% of whom were African-Americans, participated in the March and made their way to the Lincoln Memorial. Speeches by prominent civil rights leaders were interspersed with musical performances by Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Marian Anderson, Mahalia Jackson, and others. The March would close with an address by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

A Dream Becomes A Reality

Dr. King gave his “I Have A Dream” speech while standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial. In the speech, he describes his soaring vision for a harmonious nation while invoking the deeply-held values first laid out for the country by the Founding Fathers. “It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream,” he said. “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'” While lasting only 16 minutes, the speech is widely considered to be one of the most inspirational – and widely quoted – speeches in history.

After the March on Washington, Dr. King along, along many other civil rights leaders, met with President Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to discuss the need for bipartisan support for a civil rights bill. In a perfect world, the bill would address the many damaging effects of racial discrimination while promoting the desegregation of public schools, banning employment discrimination, redressing constitutional rights violations, and protecting voting rights.

Although President Kennedy expressed support for the bill, the proposed Civil Rights Act was opposed in the Senate and ended in a filibuster. However, following the assassination of President Kennedy in November of 1963, President Johnson encouraged passage of the bill, citing its importance to Kennedy and to his legacy. The bill passed in both the House and the Senate, and Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law on July 2, 1964.