The Start Of The March

Religion was front and center – and not in a good way – in 1969 in Derry, the second largest city in Northern Ireland. Inequality between the Nationalists and the Unionists was rampant. Poverty was prevalent. Housing conditions were horrific. And in spite of the presence of a Nationalist majority, laws were stacked against Catholics, owing to discriminatory practices and gerrymandering. The Unionists held leadership in all council roles, and the stranglehold they had on Catholics was beginning to exact a toll.

Around this time, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), a nonpartisan organization, was formed. The NICRA included Unionist members, but was also influenced by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Sinn Fein. NICRA’s mission included defending and protecting the rights and freedom of all citizens, exposing abuses of power, informing the public of their rights, and demanding freedom of speech, assembly, and association.

Despite NICRA’s strong presence at the time, internment without trial was introduced in Northern Ireland in August 1971 as a means of attempting to eradicate the IRA. In essence, anyone suspected of belonging to a terrorist organization could be arrested on the spot, no questions asked. The British army arrested many innocent people, some of whom were removed from their own homes and taken into custody.

In response, the NICRA organized marches against unprovoked arrest and internment, despite the fact that marches were banned in Northern Ireland as of January 18, 1972. One such march, held on January 30, 1972, would become known as Bloody Sunday.

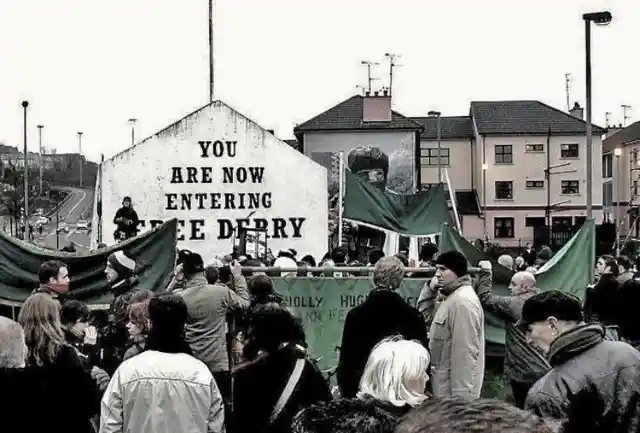

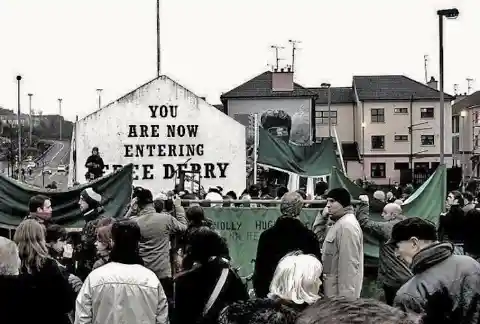

NICRA was asked to limit the march to the Catholic section of Derry, called Free Derry, defined as a “no-go” area for the British Army. Barricades that had been installed kept British military vehicles from entering this section of Ireland, and IRA members openly carried weapons as they walked about. Angered by the situation, the British Army vowed to enact stricter measures in order to better control the situation; as a result, they introduced the Parachute Regiment, which was fully deployed on Bloody Sunday.

Steps That Might Bring Change

Approximately 10,000 to 15,000 people joined the march, which began in Creggan at three in the afternoon and proceeded to the Bogside, a predominantly Catholic area just outside Derry’s Old City walls. In response to the march, the British Army erected barricades to prevent access to the city center; behind each barricade, a number of soldiers and two armored personnel carriers stood watch.

Orders were that if a protester breached the barrier, British soldiers could use cannons, rubber bullets, and tear gas to subdue the transgressor. In light of the potential conflict, march organizers changed the route, and decided to move protest to the Free Derry Corner. At the same time, British paratroopers had established a camp in a nearby abandoned building with the aim of strengthening their arrest operation.

Mayhem And Murder

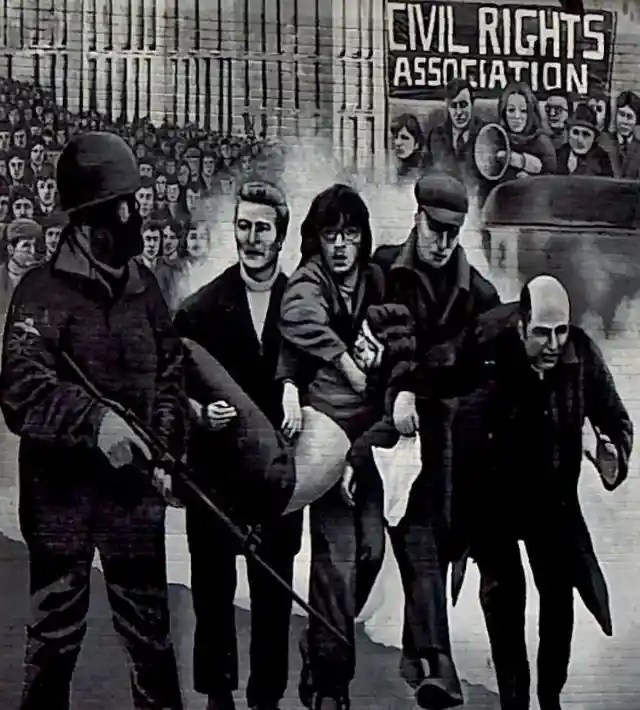

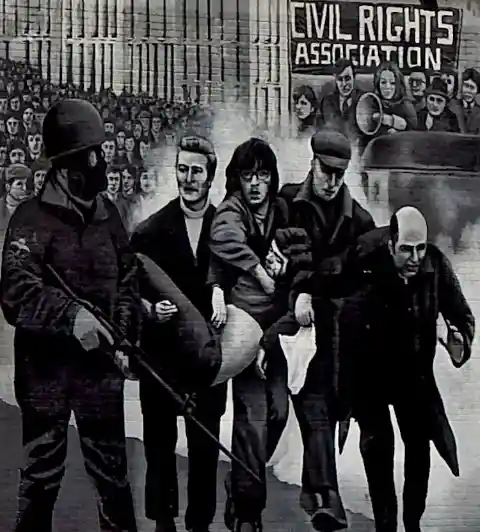

When marchers noticed the paratroopers situated in the nearby building, they began hurling stones at the military men; in response, the soldiers opened fire, injuring two marchers. The soldiers later claimed that the protesters had thrown nail bombs towards them, but no evidence was ever produced to substantiate the claim.

At 4:10, soldiers entered the Bogside in armored personnel carriers, causing many of the protestors to flee. In response, some paratroopers began capturing and beating people while others began firing rubber bullets at close range. In one clash, soldiers killed six civilians and wounded one, and another six civilians were injured in a second nearby skirmish. Seventeen-year-old Jackie Duddy, who had been running alongside a priest, was shot in the back, while another group trapped in Glenfada Park experienced two fatalities and the wounding of four individuals.

Ten minutes after entering the Bogside, soldiers fired more than 100 rounds, shooting 26 people; thirteen died that day, and one victim succumbed to his injuries months later. Incidents of brutality were many, and often involved innocent victims. Bernard McGuigan had rushed to an injured man and was waving a white handkerchief to indicate that he was not involved in the protest when a British soldier shot him in the head.

The Aftermath

In many people’s minds, the events of Bloody Sunday intensified the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and led to a searing anger that incited a mob to set fire to the British Embassy located in Dublin.

Just two days after Bloody Sunday, the Widgery Enquiry was convened to examine what had transgressed during the protest. Completed 10 weeks later, the enquiry report was considered a meaningless whitewash of one of the most violent and deadly days in Ireland’s history.

In 1998, the Saville Enquiry was launched; its conclusions differed dramatically from those of the Widgery Enquiry. Seven years after it began looking into the events of Bloody Sunday, the enquiry completed its review, and later made its findings public in 2010. When the Saville report was released, then Prime Minister David Cameron apologized, saying, “What happened on Bloody Sunday was both unjustified and unjustifiable. It was wrong.”